The Two

Babylons - The Sign of the Cross - Alexander Hislop

The cross was the unequivocal symbol of

Bacchus, the Babylonian Messiah, for he was represented with a head-band covered

with crosses. It has been well noted that drama works only because

"the audience knows that it isn't true." Therefore, we sing at the

foot of the old rugged cross only because we know that the blood of

Jesus is not going to drip on us and we will not get jabbed with a

spear.

The cross, like performance

music, is the ultimate stolen sign of the temporary triumph-over of the One True God by the universal

but end-time Babylonian form of worship which will flood the world

(Revelation 18).

"We need not shrink

from admitting that candles, like incense and lustral water, were

commonly employed in pagan worship and in the rites paid to the dead.

But the Church from a very early period took them into her service, just as she adopted many other things indifferent in themselves, which

seemed proper to enhance

the splendour of

religious ceremonial.

We must not forget that most of these adjuncts to worship,

like

music, lights,

perfumes, ablutions, floral decorations, canopies, fans, screens,

bells, vestments, etc.

were not identified with any idolatrous cult in

particular;

they were common to

almost all cults.

They are, in fact, part of the natural language of mystical

expression,

and such things

belong quite as much to secular ceremonial as they do to religion.

Catholic Encyclopedia,

on Candles

Throughout the Bible music

is the ultimate sign of turning the back on the Word or the cross. As

the women worshiped Tammuz (the sun god) musically in the temple, the

men turned their back to the temple as they worshiped the real sun in

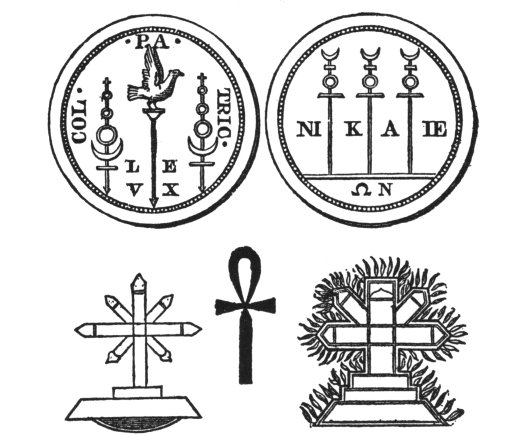

the east (Ezekiel 8). See image of Bacchus below. Notic the sign of

the cross and the instruments of Apollo (Apollyon, Abaddon, the

father of music, harmony)

Source

Source

Bishop Alexander Hislop notes that the cross as an

idol is the ultimate confession of loss of faith in the Savior who

triumphed over the cross.

Chapter V, Section

VI

See Alexander Hislop's inclusion of instrumental

music as one of these papal errors

There is yet one more symbol of

the Romish worship to be noticed, and that is the sign of the cross. In the Papal system as is well

known,

........the sign of

the cross and the image

[idol] of the cross are all in all.

No prayer can be said, no

worship engaged in, no step almost can be taken, without the frequent

use of the sign of the cross.

The cross is looked

upon as the grand

charm, as the great

refuge in every season of danger, in every

hour of temptation as

the

infallible

preservative from all the powers of darkness.

The cross is adored with all the homage due only to the

Most

High; and for any one

to call it, in the hearing of a genuine Romanist, by the Scriptural

term, "the accursed

tree," is a

mortal

offence.

Asherah:

Also a sacred wooden pole or

image standing close to

the massebah and altar in early Shemitic sanctuaries, part of the

equipment of the temple of Jehovah in Jerusalem till the reformation

of Josiah (2 Kings 23:6). The plural, 'asherim, denotes statues,

images, columns, or pillars; translated in the Bible by "groves."

Maachah, the grandmother of Asa, King of Jerusalem, is accused of

having made for herself such an idol, which was a phallus. Called the

Assyrian Tree of Life, "the original Asherah was a pillar with seven

branches on each side

surmounted by a globular flower with three projecting rays, and no

phallic stone, as the Jews made of it, but a metaphysical symbol.

'Merciful One, who dead to life raises!' was the prayer uttered

before the

Asherah, on the banks

of the Euphrates. See Ezekiel 31. Assyria is the "tallest tree in

Eden." Babylonia

Resources

To say that such

superstitious feeling for the sign of the cross, such worship as

Rome pays to a wooden or a metal cross, ever grew out of the saying

of Paul, "God forbid that I should glory, save in the cross of our

Lord Jesus Christ"--that is, in the doctrine of Christ crucified--is a mere absurdity, a shallow subterfuge and

pretence. The magic virtues attributed to the so-called

sign of the cross, the worship bestowed on

it, never came from

such a source.

When Paul choose to

"know

only Christ and Him crucified" he did not say "preach only Christ and Him

crucified." His message was that a believer should submit as Christ

(God) submitted Himself to the cruel cross. However, Paul did not

glory in the execution of Christ.

The same sign of the cross that

Rome now worships was used in the Babylonian Mysteries, was applied by Paganism to the same magic purposes, was honoured with the

same honours.

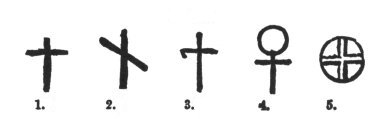

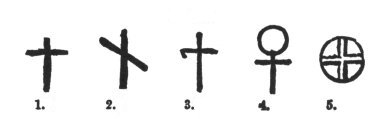

That which is now called the

Christian cross was originally no Christian emblem at all, but was the mystic Tau of the Chaldeans and Egyptians--the true original form of the letter

T--the initial of the name of

Tammuz--which, in Hebrew, radically the same

as ancient Chaldee, was found on coins, was formed as in No. 1 of the

accompanying woodcut (Fig. 43); and in Etrurian and Coptic, as in

Nos. 2 and 3. That mystic Tau was marked in baptism on the foreheads of those initiated in the Mysteries, * and was used

in every variety of way as a most sacred symbol. See

the worship of Tammuz in the temple in Jerusalem.

* TERTULLIAN, De Proescript. Hoeret. The language of Tertullian implies that those who

were initiated by baptism

in the Mysteries were marked on the forehead in the same way, as his Christian countrymen in

Africa, who had begun by this time to be marked in baptism with

the sign of the

cross.

[Note: the sign of the cross is in 6 steps, this is repeated three times to mark

666 on the forehead of unsinning infants.

Well, that is one act actually called a sign of the cross which was

the ultimate weapon of the beast which failed.

The "Mark" brands the forehead

or Mind when we make it into an idol.]

The jews attempted to seduce

Jesus into the dionysus song and dance as they "piped." Jesus also

indicated that they hoped that John wore the soft clothing of a

king's catamite or male homosexual. The worship of Dionysus was

rampant and this TRIUMPH over of Jesus would prove whether He was the

incarnate Dionysus. While He refused to engage in their traditiona

antics of all priesthoods, they nevertheless TRIUMPH OVER Him

momentarily on the cross:

"It is strange, yet

unquestionably a fact, that in ages long before the birth of Christ,

and since then in lands untouched by the teaching of the Church, the

Cross has been used as a sacred symbol. . . . The Greek

Bacchus, the Tyrian Tammuz, the Chaldean Bel,

and the Norse Odin,

were all symbolized to their votaries by a cruciform device."The

Cross in Ritual, Architecture, and Art (London, 1900), G. S. Tyack,

p. 1.

The people of the ancient lands

used the cross in

worship, some, like the

Egyptians used it in Phallus

worship, or, worship of

the male sex organ. It was used as a symbol of fertility.

"Various figures of crosses are found everywhere on Egyptian

monuments and tombs, and are considered by many authorities as

symbolical either of the phallus [a representation of the male sex

organ] or of coition. . . . In Egyptian tombs the crux ansata [cross

with a circle or handle on top] is found side by side with the

phallus." A Short History of Sex-Worship (London, 1940), H. Cutner,

pp. 16, 17; see also The Non-Christian Cross, p. 183.

W. E. Vine says on this

subject: "STAUROS (staur¬V) denotes, primarily, an

upright pale or

stake. On such

malefactors were nailed for execution. Both the noun and the verb

stauroo, to fasten to a stake or pale, are originally to be

distinguished from the ecclesiastical form of a two beamed cross."

Greek scholar Vine then mentions the Chaldean origin of the two-piece

cross and

how it was adopted

from the pagans

by Christendom in the third

century

C.E. as a symbol of

Christ's impalement." Vine's Expository Dictionary of Old and New

Testament Words, 1981, Vol. 1, p. 256.

Sustauroo (g4957) soos-tow-ro'-o; from 4862 and

4717; to impale in company with (lit. or fig.): - crucify with.

Stauroo (h4717) stow-ro'-o, from 4716; to

impale on the cross; fig. to extinguish (subdue) passion or

selfishness: - crucify.

The early Christians did not

think to have a crucifix or a cross hanging on their doors or in

their places of meeting. New Catholic Encyclopedia says: "The

representation of Christ's redemptive death on Golgotha does not

occur in the symbolic art of the first Christian centuries. The early

Christians, influenced by the Old Testament prohibition of graven

images, were reluctant to depict even the instrument of the Lord's

Passion." (1967), Vol. IV, p. 486

A History of the Christian

Church says: "There was no use of the crucifix and no material

representation of the cross." (New York, 1897), J. F. Hurst, Vol. I,

p. 366. Resource

Therefore, too much focus on the cross and steeples

may be a subconscious confession. See the cross connection of

feminine or effeminate religion.

To identify Tammuz with the sun it

was joined sometimes to the circle of the sun as in No. 4; sometimes

it was inserted in the circle, as in No. 5. Whether the Maltese

cross, which the Romish

bishops append to their names as a symbol of their episcopal

dignity, is the letter

T, may be doubtful; but there seems no

reason to doubt that that Maltese cross is an express symbol of the

sun; for Layard found it as a sacred symbol in Nineveh in such a

connection as led him to identify it with the sun.

The mystic Tau, as the symbol of the great divinity, was called

"the sign of life"; it was used as an amulet over the heart; it was

marked on the official garments of the priests, as on the official

garments of the priests of Rome; it was borne by kings in their hand,

as a token of their dignity or divinely-conferred authority. The Vestal virgins of Pagan Rome wore it suspended

from their necklaces, as the nuns do now.

- The winged

phallus was worn as a pendant: it is similar to the ANK

-

The Egyptians did the same, and many of the barbarous nations with

whom they had intercourse, as the Egyptian monuments bear witness. In

reference to the adorning of some of these tribes, Wilkinson thus

writes: "The girdle was sometimes highly ornamented; men as well as

women wore earrings; and they frequently had a small cross suspended to a necklace, or to the collar of their dress. The adoption of

this last was not peculiar to them; it was also appended to, or

figured upon, the robes of the Rot-n-no; and traces of it may be seen

in the fancy ornaments of the Rebo, showing that it was already in

use as early as the

fifteenth century before the Christian era." (Fig. 44).

[Note: the

Israelites carried along their idols from Egypt and the women wore

earings and other jewelry which was almost always an image of the

"god" or "goddess." The women had spent 400 years worshiping Osiris pictured as a tiny or large golden calf. The

Israelites turned their back on the Book of the Covenant to make this

image which they worshiped with singing, dancing naked and musical

instruments (the word play in

Hebrew). Because the Spirit of Christ was the Spirit in the

Wilderness giving them a covenant of Grace, when the people turned

back to Egyptian worship they turned their back on Christ and

worshiped the image rather than the Creator.

Apis was the beast-god of ancient Egypt. He

was also known as Mnevis,

and Onuphis. Apis / Mnevis / Onuphis (Apis) was regarded as the

avatar or Incarnation of the god Osiris, whose soul it was said had

transmigrated into the body of a bull.]

There is hardly a Pagan tribe where the cross has not

been found. The cross

was worshipped by the Pagan Celts long before the incarnation and

death of Christ. "It is a fact," says Maurice,

"not less

remarkable than well-attested, that the Druids in their groves were

accustomed to select the most stately and beautiful tree as an emblem

of the Deity they adored, and having cut the side branches, they affixed two of the largest of them to the

highest part of the trunk, in such a manner that those branches extended on each side like the arms of a man, and, together with the body, presented

the appearance of a HUGE CROSS, and on the bark, in several places,

was also inscribed the letter Thau."

It was worshipped in

Mexico for ages before the Roman Catholic missionaries set foot there, large

stone crosses being erected, probably to the "god of rain."

The cross thus

widely worshipped, or regarded as a sacred emblem,

was the unequivocal symbol of Bacchus, the Babylonian Messiah, for he was represented with a head-band covered

with crosses. (Fig 45) ||

|| The above figure is the head.. only magnified,

that the crosses may be more distinctly visible. The worship at Rome

on Good Friday of the 'cross of fire,' brings the full significance of that worship to

view.

|

|

THE SWASTIKA, placed in the

emblem at the head of the serpent, found. It is the fiery cross, with arms of

whirling

flame

revolving clockwise to represent the tremendous energies

of nature incessantly creating and dissolving the forms

through which the evolutionary process takes place. In

religions which recognise three aspects of Deity, the

swastika is associated with the Third Person of the

Trinity, who is at once the Creator and the Destroyer:

Shiva in Hinduism and the Holy Ghost in Christianity.

Applied to humanity, the figure may show the human as the

link between heaven and earth, one "hand" pointing toward

heaven or spirit and the other toward earth or matter.

Source

|

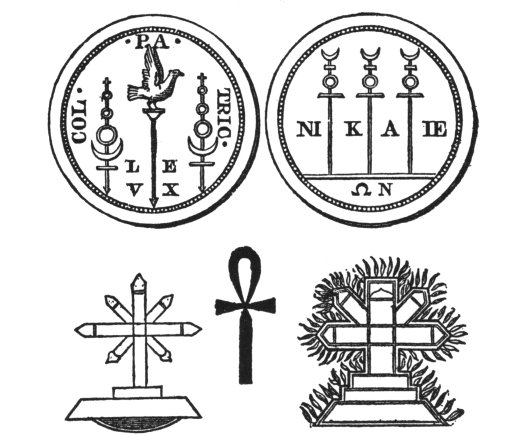

This symbol of the Babylonian god is reverenced at this day in all the

wide wastes of Tartary, where Buddhism prevails, and the way in which it is represented

among them forms a striking commentary on the language applied by

Rome to the Cross. "The cross," says Colonel Wilford, in the

Asiatic

Researches, "though not

an object of worship

among the Baud'has or Buddhists, is a favourite emblem and device among

them. It is exactly the cross of the Manicheans, with leaves and

flowers springing from it.

This cross, putting forth

leaves and flowers (and fruit also, as I am told), is called the

divine tree, the tree of the gods, the tree of life and knowledge, and productive of whatever is good and

desirable, and is placed in the terrestrial paradise." (Fig.

46)

Compare this with the language of Rome applied to the cross, and it will be seen how exact

is the coincidence. In the Office of the Cross, it is called the

"Tree of life," and the worshippers are taught thus to address it:

"Hail, O Cross,

triumphal

wood, true salvation of

the world, among trees

there is none like thee in leaf, flower, and bud...O Cross,

our only

hope, increase

righteousness to the godly and pardon the offences of the guilty."

*

* The above was actually

versified by the Romanisers in the Church of England, and

published along with much besides from the same source, some years

ago, in a volume entitled Devotions on the Passion. The London Record, of April, 1842, gave the following as a specimen of

the "Devotions" provided by these "wolves in sheep's clothing" for

members of the Church of England:--

"O faithful cross, thou peerless tree,

No forest yields the like of thee,

Leaf, flower, and bud;

Sweet is the wood, and sweet the weight,

And sweet the nails that penetrate

Thee, thou sweet wood."

Can any one, reading the gospel narrative of the

crucifixion, possibly believe that that narrative of itself could

ever germinate into such extravagance of "leaf, flower, and bud," as

thus appears in this Roman Office? But when it is considered that the

Buddhist, like the Babylonian cross, was the recognised

emblem of Tammuz (Eze

8:14), who was known as

the mistletoe branch, or "All-heal," then it is easy to see how the

sacred Initial should be represented as covered with leaves, and how

Rome, in adopting it, should call it the

"Medicine which

preserves the healthful, heals the sick, and does what mere human

power alone could never do."

Now, this Pagan symbol seems first to have crept into the Christian

Church in Egypt,

and generally into Africa. A statement of Tertullian, about the

middle of the third century, shows how much, by that time, the Church

of Carthage was infected with the old leaven. Egypt especially,

which was never thoroughly evangelised, appears to have taken the

lead in bringing in this Pagan symbol. The first form of that which

is called the Christian

Cross, found on

Christian monuments there, is the unequivocal Pagan

Tau, or Egyptian "Sign of life." Let the

reader peruse the following statement of Sir G. Wilkinson:

"A still more

curious fact may be mentioned respecting this hieroglyphical

character [the Tau], that the early Christians of Egypt adopted it in

lieu of the cross, which was afterwards substituted for it, prefixing it to inscriptions in

the same manner as the cross in later times. For, though Dr. Young had some scruples in

believing the statement of Sir A. Edmonstone, that it holds that

position in the sepulchres of the great Oasis,

I can attest that such is the case, and that numerous inscriptions,

headed by the Tau,

are preserved to the present day on early Christian monuments."

The drift of this statement is

evidently this, that in Egypt the earliest form of that which has

since been called

the cross, was no other than the "Crux Ansata," or "Sign of life," borne by Osiris and all the Egyptian gods; that the ansa or "handle" was afterwards dispensed with, and that

it became the simple Tau, or ordinary cross, as it appears at this

day, and that the design of its first employment on the sepulchres,

therefore, could

have no reference to the crucifixion of the Nazarene,

but was simply the result of the attachment to old and long-cherished

Pagan symbols,

which is always strong in those who, with the adoption of the

Christian name and profession,

are still, to a large extent, Pagan in heart and feeling. This, and this only, is the origin of

the worship of the "cross."

|

"Yet the cross itself is the

oldest of phallic emblems, and the lozenge-shaped windows of

cathedrals are proof that the yonic symbols have survived

the destructions of the pagan Mysteries. The very structure

of the church itself is permeated with (sexual symbolism)

phallicism. Remove from the Christian Church all emblems of

Priapic origin and nothing is left..." -The secret teaching of all ages by Manley P.

Hall "Yet the cross itself is the

oldest of phallic emblems, and the lozenge-shaped windows of

cathedrals are proof that the yonic symbols have survived

the destructions of the pagan Mysteries. The very structure

of the church itself is permeated with (sexual symbolism)

phallicism. Remove from the Christian Church all emblems of

Priapic origin and nothing is left..." -The secret teaching of all ages by Manley P.

Hall

|

The priests female wardrobe

is a phallic symbol: the Red Hat caps it off.

See

some other "christian" symbols.

-

- THE CENTRE of the

seal is the ankh or Crux Ansata, an ancient Egyptian symbol of

resurrection. It is composed of the Tau or

T&endash;shaped cross surmounted by a small circle and is

often seen in Egyptian statuary and in wall and tomb

paintings where it is depicted as being held in the hand.

The Tau symbolises matter or the world of form; the small

circle above it represents spirit or life. With the

circle marking the position of the head, it represents

the mystic cube unfolded to form the Latin cross, symbol

of spirit descended into matter and crucified thereon,

but risen from death and resting triumphant on the arms

of the conquered slayer. So it may be said that the

figure of the interlaced triangles enclosing the ankh

represents the human triumphant and the divine triumphant

in the human. As the cross of life, the ankh then becomes

a symbol of resurrection and mmortality. Source

-

- Another view: The Ankh represents the

genitals of both sexes. The cross itself is a primitive

form of the phallus, and the loop that of the womb.

Again, we continue the symbol of the cross as the giver

of life. Yes...even prior to this time was the cross a

symbol of the phallus or fertility. This is not the only

thing that the phallus has symbolized over the many

centuries within and without the pagan world. It has also

been used as a symbol of strength.

|

This, no doubt, will appear all very strange and very

incredible to those who have read Church history, as most have done

to a large extent, even amongst Protestants, through Romish

spectacles; and especially to those who call to mind the famous story

told of the miraculous appearance of the cross to Constantine on the day before the decisive victory at the

Milvian bridge, that decided the fortunes of avowed Paganism and nominal

Christianity. That story, as commonly told, if true, would certainly

give a Divine sanction to the reverence for the cross.

But that story, when sifted to

the bottom, according to the common version of it, will be found to

be based on a delusion--a delusion, however, into which so good a man

as Milner has allowed himself to fall. Milner's account is as

follows: "Constantine, marching from France into Italy against

Maxentius, in an expedition which was likely either to exalt or to

ruin him, was oppressed with anxiety. Some god he thought needful to

protect him; the God of the Christians he was most inclined to

respect, but he wanted some satisfactory proof of His real existence

and power, and he neither understood the means of acquiring this, nor

could he be content with the atheistic indifference in which so many

generals and heroes since his time have acquiesced.

He prayed, he

implored with such vehemence and importunity, and God left him not

unanswered. While he was marching with his forces in the afternoon,

the trophy of the cross appeared very luminous in the heavens,

brighter than the

sun, with this

inscription, 'Conquer by this.'

He and his soldiers were

astonished at the sight; but he continued pondering on the event till

night. And Christ appeared to him when asleep with the same sign of

the cross, and directed him to make use of the symbol as his military

ensign." Such is the statement of Milner. Now, in regard to the

"trophy of the cross," a

few words will suffice to show that it is utterly

unfounded. I do not

think it necessary to dispute the fact of some miraculous sign having

been given. There may, or there may not, have been on this occasion a

"dignus vindice

nodus," a crisis worthy

of a Divine interposition. Whether, however, there was anything out

of the ordinary course, I do not inquire. But this I say, on the

supposition that Constantine in this matter acted in good faith,

and that there actually was a

miraculous appearance in the heavens, that it as not the sign of the

cross that was seen, but quite a different thing, the name of Christ. That this was the case, we have at once

the testimony of Lactantius, who was the tutor of Constantine's son

Crispus--the earliest author who gives any account of the matter, and

the indisputable evidence of the standards of Constantine themselves,

as handed down to us on medals struck at the time. The testimony of

Lactantius is most decisive: "Constantine was warned in a dream to

make the celestial sign of God upon his solders' shields, and so to

join battle. He did as he was bid, and with the transverse letter X

circumflecting the head of it, he marks Christ

on their shields. Equipped with this sign, his army takes the sword."

Now, the letter X was just the initial of the name of Christ, being equivalent in Greek to

CH. If, therefore, Constantine did as he

was bid, when he made "the celestial sign of God" in the form of "the

letter X," it was that "letter X," as the symbol of "Christ" and not the

sign of the cross, which he saw in the heavens. When the Labarum, or

far-famed standard of Constantine itself, properly so called, was

made, we have the evidence of Ambrose, the well-known Bishop of

Milan, that that standard was formed on the very principle contained

in the statement of Lactantius--viz., simply to display the

Redeemer's

name. He calls it

"Labarum, hoc est Christi sacratum nomine signum."--"The Labarum,

that is, the ensign consecrated by the NAME of Christ." *

* Epistle of Ambrose to the Emperor

Theodosius about the proposal to restore the Pagan altar of Victory

in the Roman Senate.

The subject of the Labarum has been much confused through ignorance

of the meaning of the word. Bryant assumes

(and I was myself formerly led away by the assumption) that it was

applied to the standard bearing the crescent and the cross, but he

produces no evidence for the assumption; and I am now satisfied that

none can be produced. The name Labarum, which is generally believed

to have come from the East, treated as an Oriental word, gives forth

its meaning at once. It evidently comes from Lab, "to vibrate," or "move to and fro," and

ar "to be active." Interpreted thus,

Labarum signifies simply a banner or flag, "waving to and fro" in the

wind, and this entirely agrees with the language of Ambrose "an

ensign consecrated by the name of Christ," which implies a banner.

There is not the slightest

allusion to any cross--to anything but the simple name of Christ.

While we have these testimonies of Lactantius and Ambrose, when we

come to examine the standard of Constantine, we find the accounts of

both authors fully borne out; we find that that standard, bearing on

it these very words, "Hoc signo victor eris," "In this sign thou shalt be a conqueror," said to

have been addressed from heaven to the emperor, has nothing at all in

the shape of a cross, but "the letter X." In the Roman Catacombs, on

a Christian monument to "Sinphonia and her sons," there is a distinct

allusion to the story of the vision; but that allusion also shows

that the X, and not the cross, was regarded as the "heavenly sign."

The words at the head of the inscription are these:

"In Hoc Vinces [In

this thou shalt overcome] X."

Nothing whatever but the X is here given as the

"Victorious Sign." There are some examples, no doubt, of

Constantine's standard, in which there is a cross-bar, from which the flag is suspended, that contains

that "letter X"; and Eusebius, who wrote when superstition and

apostacy were

working, tries hard to make it appear that that cross-bar was the

essential element in the ensign of Constantine. But this is obviously

a mistake; that cross-bar was nothing new, nothing peculiar to

Constantine's standard.

Tertullian shows

that that cross-bar was found long before on the vexillum, the Roman Pagan standard, that carried a flag; and it was used

simply for the purpose of displaying that flag. If, therefore, that

cross-bar was the "celestial sign," it needed no voice from heaven to direct

Constantine to make it; nor would the making or displaying of it have

excited any particular attention on the part of those who saw it.

We find no evidence at all that

the famous legend,

"In this overcome," has any reference to this cross-bar; but we find

evidence the most decisive that that legend does refer to the X. Now,

that that X was not intended as the sign of the cross, but as the

initial of Christ's name, is manifest from this, that the Greek P,

equivalent to our R, is inserted in the middle of it, making by their

union CHR. The standard of Constantine, then, was just the

name of Christ. Whether the device came from

earth or from heaven--whether it was suggested by human wisdom or

Divine, supposing that Constantine was sincere in his Christian

profession, nothing more was implied in it than a literal embodiment

of the sentiment of the Psalmist, "In the name of the Lord will we display our banners." To display

that name on the standards of Imperial Rome was a thing absolutely

new; and the sight of that name,

there can be little doubt, nerved the Christian soldiers in

Constantine's army with more than usual fire to fight and conquer at

the Milvian bridge.

In the above remarks I have

gone on the supposition that Constantine acted in good faith as a

Christian. His good faith, however, has been questioned; and I am not

without my suspicions that the X may

have been intended to have one meaning to the Christians and another

to the Pagans. It is certain that the X was the symbol of the god Ham

in Egypt, and as such was exhibited on the breast of his image.

Whichever view be taken, however, of Constantine's sincerity, the

supposed Divine warrant for reverencing the sign of the cross

entirely falls to the ground. In regard to the X, there is no doubt

that, by the Christians who knew nothing of secret plots or devices,

it was generally taken, as Lactantius declares, as equivalent to the

name of "Christ." In this view, therefore, it had no very great

attractions for the Pagans, who, even in worshipping Horus, had

always been accustomed to make use of the mystic tau or cross, as the

"sign of life," or the magical charm that secured all that was good,

and warded off everything that was evil. When, therefore, multitudes

of the Pagans, on the conversion of Constantine, flocked into the

Church, like the semi-Pagans of Egypt, they brought along with them

their predilection for the old symbol. The consequence was, that in

no great length of time, as apostacy proceeded, the X which in itself

was not an unnatural symbol of Christ, the true Messiah, and which

had once been regarded as such, was allowed to go entirely into

disuse, and the Tau, the sign of the cross, the indisputable sign of

Tammuz, the false Messiah, was everywhere substituted in its stead. Thus, by the "sign of the cross,"

Christ has been crucified anew by those who profess to be His

disciples. Now, if these things be matter of historic fact, who can

wonder that, in the Romish Church, "the sign of the cross" has always

and everywhere been seen to be such an instrument of rank

superstition and delusion?

There is more, much more, in

the rites and ceremonies of Rome that might be brought to elucidate

our subject. But the above may suffice. *

* If the above

remarks be well founded, surely it cannot be right that this sign of

the cross, or emblem of Tammuz, should be used in Christian baptism.

At the period of the Revolution, a Royal Commission, appointed to

inquire into the Rites and Ceremonies of the Church of England,

numbering among its members eight

or ten bishops, strongly recommended that the

use of the cross, as tending to superstition, should be laid aside.

If such a recommendation was given then, and that by such authority

as members of the Church of England must respect, how much ought that

recommendation to be enforced by the new light which Providence has

cast on the subject!

Notes from Section

4.2

It is not in one point only,

but in manifold respects, that the ceremonies of "Holy Week" at Rome,

as it is termed, recall to memory the rites of the great Babylonian god. The more we look at these rites, the

more we shall be struck with the wonderful resemblance that subsists

between them and those observed at the Egyptian festival of burning

lamps and the other ceremonies of the fire-worshippers in different

countries.

In Egypt the grand illumination took place beside the sepulchre of Osiris at

Sais.

........ In Rome in "Holy Week," a sepulchre of

Christ also figures in connection with a brilliant illumination of

burning tapers.

In Crete, where the tomb of

Jupiter was exhibited, that tomb was an object of worship to the

Cretans.

........ In Rome, if the devotees do not worship

the so-called sepulchre of Christ, they worship what is entombed

within it.

As there is reason to believe

that the Pagan festival of burning lamps was observed in

commemoration of the ancient fire-worship, so there is a ceremony at Rome in the Easter week,

which is an unmistakable act of fire-worship, when a

cross of

fire is the grand

object of worship.

This ceremony is thus

graphically described by the authoress of Rome in the 19th Century:

"The effect of the

blazing cross of fire suspended from the dome above the confession or tomb

of St. Peter's, was strikingly brilliant at night.

It is covered with innumerable lamps, which have the effect of one

blaze of fire...

The whole church was thronged

with a vast multitude of all classes and countries, from royalty to

the meanest beggar, all gazing upon this one object. In a few minutes

the Pope and all his Cardinals descended into St. Peter's, and room being kept for them by

the Swiss guards, the aged Pontiff...prostrated himself in silent

adoration before the CROSS

OF FIRE. A long train of Cardinals knelt before

him, whose splendid robes and attendant train-bearers, formed a

striking contrast to the humility of their attitude." What could be a

more clear and unequivocal act of fire-worship than this? Now, view this in connection

with the fact stated in the following extract from the same work, and

how does the one cast light on the other:

"With Holy Thursday our

miseries began [that is, from crowding]. On this disastrous day we

went before nine to the Sistine chapel...and beheld a procession led

by the inferior orders of clergy, followed up by the Cardinals in

superb dresses, bearing long wax tapers in their hands, and ending

with the Pope himself, who walked beneath a crimson canopy, with his

head uncovered,

bearing the Host

in a box; and this

being, as you know,

the real flesh and blood of Christ, was carried from the Sistine

chapel through the intermediate hall to the Paulina chapel, where it

was deposited in the sepulchre prepared to receive it beneath the

altar...

I never could learn why

Christ was to be buried

before He was dead,

for,

........ as the crucifixion did not take place

till Good Friday,

........ it seems odd to inter Him on

Thursday.

His body, however, is laid in

the sepulchre, in all the churches of Rome, where this rite is

practised, on Thursday forenoon, and it remains there till Saturday

at mid-day, when, for some reason best known to themselves,

He is supposed to

rise from the grave amidst the firing of cannon, and blowing of trumpets, and jingling of bells,

which have been

carefully tied up ever since the dawn of Holy Thursday, lest the

devil should get into them."

The worship of the cross of

fire on Good Friday explains at once the anomaly otherwise so

perplexing, that Christ should be buried on Thursday, and rise from

the dead on Saturday.

If the festival of

Holy Week be really, as

its rites declare,

one of the old

festivals of

Saturn, the

Babylonian

fire-god, who, though

an infernal god, was yet Phoroneus, the great "Deliverer,"

it is altogether

natural that the god of the Papal idolatry, though called by Christ's

name, should rise from the dead on his

own day--the Dies Saturni, or "Saturn's day." *

* The above account referred to

the ceremonies as witnessed by the authoress in 1817 and 1818. It

would seem that some change has taken place since then, caused

probably by the very attention called by her to the gross anomaly

mentioned above; for Count Vlodaisky, formerly a Roman Catholic

priest, who visited Rome in 1845,

has informed me

that in that year the

resurrection took place,

not at mid-day, but at nine o'clock on the evening of Saturday.

This may have been intended to

make the inconsistency between Roman practice and Scriptural fact

appear somewhat less glaring.

Still the fact

remains, that the resurrection of Christ, as celebrated at Rome,

takes place,

not on His own day--"The Lord's day"--but--on the day of Saturn, the god of

fire!

On the day before the

Miserere is sung with such overwhelming pathos,

that few can listen to it unmoved, and many even swoon with the

emotions that are excited. What if this be at bottom only the

old song of

Linus, of whose very

touching and melancholy character Herodotus speaks so strikingly?

Certain it is, that much of the pathos of that Miserere depends on the part borne in singing it by the

sopranos; and equally certain it is that Semiramis, the wife of him who, historically, was the original

of that god whose tragic death was so pathetically celebrated in many

countries, enjoys the fame, such as it is, of having been the

inventress of the practice from which soprano singing took its rise.

See Frazer's Comments on Bells and

Superstition

See the Clang and Gongs of 1 Corinthians

13

Hislop Table of Contents

Home Page

"Yet the cross itself is the

oldest of phallic emblems, and the lozenge-shaped windows of

cathedrals are proof that the yonic symbols have survived

the destructions of the pagan Mysteries. The very structure

of the church itself is permeated with (sexual symbolism)

phallicism. Remove from the Christian Church all emblems of

Priapic origin and nothing is left..." -The secret teaching of all ages by Manley P.

Hall

"Yet the cross itself is the

oldest of phallic emblems, and the lozenge-shaped windows of

cathedrals are proof that the yonic symbols have survived

the destructions of the pagan Mysteries. The very structure

of the church itself is permeated with (sexual symbolism)

phallicism. Remove from the Christian Church all emblems of

Priapic origin and nothing is left..." -The secret teaching of all ages by Manley P.

Hall